This episode originally aired on Dec. 20, 2024.

We're doing something a little different for this episode. After a year of taking questions from our adult listeners across Montana and beyond, The Big Why team thought it would be fun to see what kids are curious about.

Our journey on this first episode of 'The Little Why' starts in Ms. Baroch-Wallin's third-grade classroom at Daly Elementary School in Hamilton. Our Community Engagement Specialist Katy Wade and I visited the class for the first time in mid-October. The room was plastered with colorful artwork, drawings and words of encouragement, coats and backpacks hung from hooks on the back wall and lurking in the corner ...

Student: Have you seen our pet jumping spider?

Austin Amestoy: You guys have have a pet jumping spider?

Katy and I introduced ourselves, answered some questions about how radio works, and explained what the students would do on our first visit.

Katy Wade What we're here to do today is to kind of see if you guys have any fun questions that we could ask and then maybe hopefully decide on just one question, our favorite question, and then we're going to come back in a couple of weeks and we're going to teach you all the answer. Does that sound like fun?

Austin Amestoy: Ms. Baroch-Wallin split the students into groups. They shove their chairs aside and they were off. No surprise, the students were full of questions. Here's Zane Jessup.

Zane Jessup Um, how, how did Montana get the mountains?

Austin Amestoy: Why does that question make you curious?

Zane Jessup Because what's good about the mountains that they [indecipherable] But I don't know how they got there.

Austin Amestoy: Claire Bryan had a question that I'm very eager for us to dive into some day.

Claire Bryan Why is Helena the capital of Montana?

Austin Amestoy: But after everyone got back to their seats and voted for their favorite question, there was a clear winner, a question about a favorite fascination of kids as old as time. 'Why was the first dinosaur found in Montana?'.

Austin Amestoy: Lucky for Katy and me, Montana is chock full of fossil experts, including one who lives not too far from Daly Elementary. We brought her along on our return trip to Hamilton a few weeks after our first visit.

Kallie Moore: Hi, everybody. My name is Kallie, and I manage the paleontology collection at the University of Montana. So I'm like a fossil librarian.

Austin Amestoy: Kallie Moore is also host of the popular PBS YouTube show Eons, and recently published a children's book titled "Tales of the Prehistoric World. Adventures from the Land of Dinosaurs." Kind of a perfect match to bring back to the classroom.

Kallie Moore: So everything that your book librarian does here in your school, I basically do that for fossils at the university. So I keep them conserved, I keep them safe, I keep them available for researchers, I send them all over the world so people can study them. So it's a pretty fun job.

Austin Amestoy: As a fossil librarian, Moore has to command knowledge of all types of prehistoric creatures, not just dinos. But as we discussed in an interview after our visit to the classroom, kids and adults alike have an insatiable curiosity for those terrible lizards.

Kallie Moore: I work with the public so much if I let my dinosaur info lax, like, they're going to ask me questions about stuff I've never even heard of before, so I kind of have to stay up on it.

Austin Amestoy: Or when you have to, like, face a tribunal of third grade kids.

Kallie Moore: Yeah, exactly.

Austin Amestoy: Moore definitely came prepared to answer the students' main question and a slew of others. First off, it's important to note that the scientists who first named a dinosaur they found in Montana weren't the first people to find dinosaurs here. That honor belongs to the Indigenous people who first called the mountains and plains home. Indigenous fossil discoveries may have inspired tales like the Thunderbird or Water Monster in Sioux creation stories. European settlers brought new scientific study methods to the Americas, including a fascination with the bones of huge creatures buried beneath us. And Montana was no slouch when it came to improving our understanding of those ancient animals.

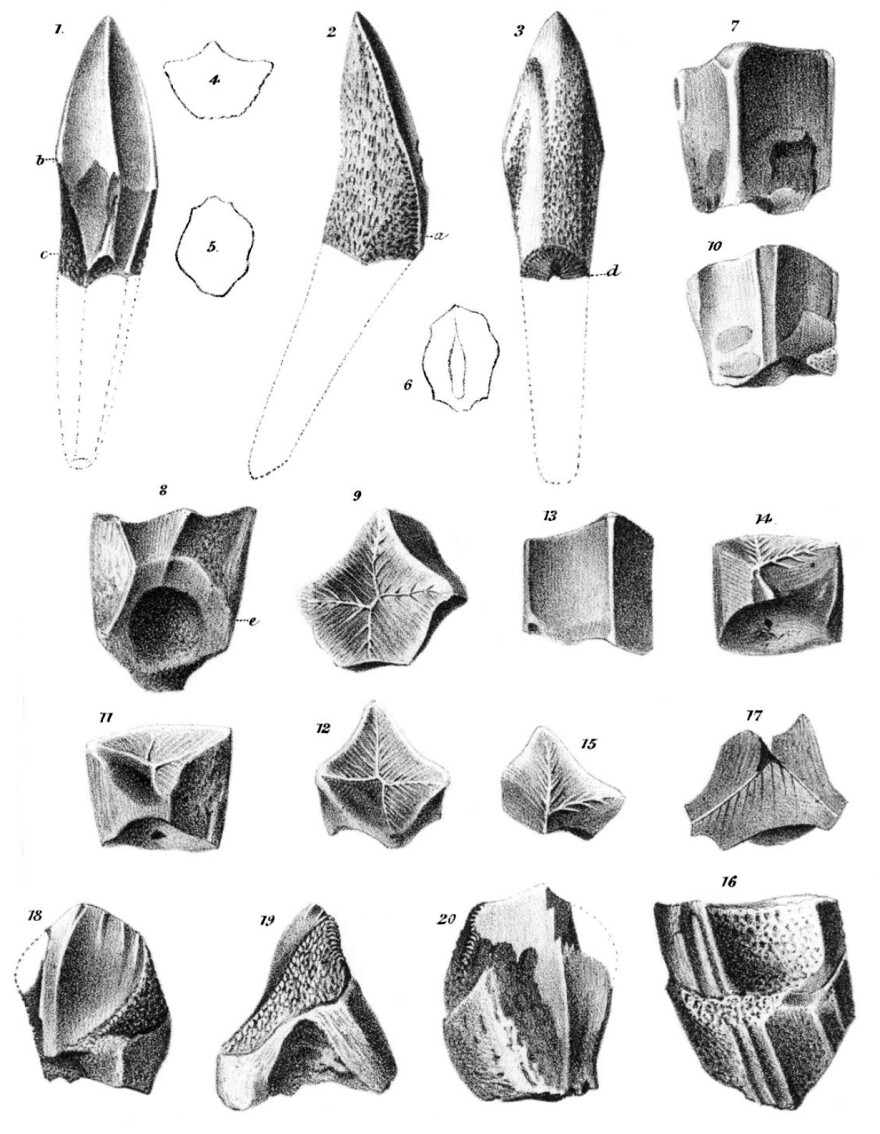

Kallie Moore: Montana's first dinosaur is also North America's first named dinosaur, which is super cool, and they were found here in Montana in 1854. So there was a naturalist named Ferdinand Hayden that went out and explored this part of the country looking for bones and fossils.

Austin Amestoy: Hayden spent much of his life surveying the Western U.S. for its geology and fossils. Moore says eastern Montana's rolling plains were a perfect place to search for bones. It's easier to find fossils in exposed environments like deserts or badlands, and Hayden found them, literally a handful of them, near Judith Landing in the Missouri River Breaks. They were teeth that belonged to a duckbill dinosaur.

Kallie Moore: Who knows what a duckbill dinosaur looked like? Can any of you name a duck-billed dinosaur?

Student: Pteranodon.

Kallie Moore: Oh, yeah. How about another one?

Student: Triceratops?

Kallie Moore: Nope. That's not a duck-billed dinosaur.

Student: A dodo?

Kallie Moore: Nope. That one's modern. So duckbill dinosaurs are like hadrosaur or parasaurolophes.

Austin Amestoy: Or, in the case of Ferdinand Hayden's fossil, find something else entirely. Hayden sent his handful of teeth to his colleague Joseph Leidy, who identified them as belonging to a duck-billed dinosaur he dubbed trachodon, meaning "rough tooth."

Kallie Moore: Now, let me show you. I brought some things with me to help you visualize some of these fossils. So those teeth that Hayden found looked a lot like these.

Austin Amestoy: More walked around with the replica tooth. It's brown and slightly curved, about the size of a potato chip. The students took turns, feeling it for themselves.

Kallie Moore: So this is what the dinosaur used to chew up the food.

Austin Amestoy: More told me later that Hayden's find, Montana and North America's first named dinosaur, is actually still debated to this day.

Kallie Moore: And what's fun about the teeth, so, this dinosaur was discovered on isolated teeth. And when we look back at those isolated teeth, about half of them do belong to a hadrosaur, a duck-billed dinosaur. But the other half actually belonged to a triceratops.

Austin Amestoy: Of the ones that were discovered?

Kallie Moore: Yeah. So the type specimen of trachodon, these isolated teeth, are actually two separate dinosaurs completely, already. Which is kind of fun. So, I mean, we didn't know. We didn't know.

Austin Amestoy: More says that's just the name of the game when it comes to scientific discovery. What we think we know often changes as we gather more evidence. Montana helped prove that point in a big way with another major dino discovery in the 1970s.

Kallie Moore: Other records, fossil records from our state, that are first for us are the first baby dinosaur bones ever found in the entire world, were found right here in Montana.

Austin Amestoy: The site just south of the town of Choteau, was discovered by a local businesswoman. She collected a handful of tiny bones and showed them to a paleontologist who visited her rock shop in the nearby town of Bynum. The complex became known as Egg Mountain after researchers uncovered at least 14 nests that contained the remains of dozens of baby Maiasaura, which means 'good mother dinosaur'. Moore says the site demonstrated that some dinosaurs cared for their young, which was a brand new idea at the time. It also hinted at how dinosaurs grow.

Kallie Moore: Now, how old are you all?

Students: Eight. Nine.

Kallie Moore: Eight and nine. Oh, that's real great. Because, maiasaura hatched at about two pounds. A little two-pound baby dinosaur could fit in my hand. How awesome would that be? But they reached an adult size of over 4,000 pounds in eight to 10 years.

Austin Amestoy: More told me later that for decades, scientists didn't even know for sure that dinosaurs laid eggs at all. Egg Mountain changed that knowledge and much more.

Kallie Moore: Yes, they laid eggs. But then we were able to look at their growth rates, how fast they could grow, because dinosaur bones grow concentricly. So they grow like tree rings. So you can slice them open, look at them underneath a microscope, and literally just count the rings and know how old they were.

Austin Amestoy: Egg Mountain was a groundbreaking find that's still generating new discoveries today. It also launched maiasauras to fame when state lawmakers honored the dinosaur a few years later.

Kallie Moore: So, hopefully, somebody is going to ask you one of these days, what's our state fossil. And what are you going to say?

Students: Maiasauras.

Kallie Moore: Yeah, very good.

Austin Amestoy: Montana's landmark fossil finds didn't end with Egg Mountain. In fact, Moore says one of the best preserved dinosaurs ever discovered was found near Malta in 2001. It still had the majority of its skin intact, including foot pads, scales ...

Kallie Moore: And even its last meal. What it ate right before it died was still preserved in the belly. So there were ferns and conifers and magnolia preserved in the belly. Magnolias are trees, but they have these big giant white balloons ...

Austin Amestoy: Moore told me it took nearly 10 years to dig up the fossilized brachylophosaurus dubbed 'Leonardo' out of the ground.

Kallie Moore: Because once they started finding skin, like you get down to where you're basically just prepping, like, removing a single sand grain from underneath a microscope. And so it was just a huge undertaking to get this specimen prepped.

Austin Amestoy: Moore said scientists believe the so-called mummy dinosaur is about 90% complete. Leonardo is considered one of the most groundbreaking fossil discoveries ever made. And that's really the theme of Montana's paleontology records. From the time Ferdinand Hayden held those trachedon and triceratops teeth in his hand scientists knew Montana was special, that the keys to unlocking the secrets of life on Earth millions of years ago could be buried right beneath them.

Austin Amestoy: After a long stretch of Q&A, our time and Ms. Baroch-Wallin's class came to an end.

That's it for this first episode of The Little Why. Special thanks to Kallie Moore, Ms. Baroch-Wallin and her inquisitive class for their excellent questions. If have a curious class of your own, or you know a teacher who does, drop us a line at www.bigwhy.org, we may just pay you a visit.

Below, you can find my full conversation with Kallie Moore, where we both nerd out about dinosaurs.

We'll be taking a few weeks to release our next episode as our reporters continue digging into your questions, with some time to enjoy the holidays, too. In the meantime, find us wherever you get your podcasts and help others find the show by sharing it and leaving us a review. Let's see what we can discover together.

-

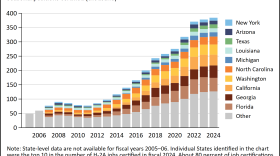

Cattle industry representatives say they need more workers. They hope expanding a foreign labor program will help. Finding adequate farm labor is one of the biggest challenges producers face.

-

Blackfeet tribal officials declared a state of emergency due to extreme winter temperatures impacting the region. The National Weather Service is forecasting a high of 6 below zero in Browning Wednesday morning, and a low of negative 13 on Wednesday night. Wind gusts may also reach up to 50 mph.

-

A Bozeman-based candidate nominated for a top U.S. Department of State job is facing bipartisan backlash after a congressional hearing last week. Members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee questioned Jeremy Carl about past statements they called racist and anti-Semitic.

-

A study finds that people who did one specific form of brain training in the 1990s were less likely to be diagnosed with dementia over the next 20 years.

-

Is America still a democracy? Scholars tell NPR that after the last year under President Trump, the country has slid closer to autocracy or may already be there.

-

The Montana GOP prioritizes judicial elections and party loyalty; Gov. Greg Gianforte and Attorney General Austin Knudsen launch an investigation over a possible violation of the state’s "sanctuary city" ban; Democratic congressional candidates try to distinguish themselves.