For this episode of The Big Why, we’re talking about salmon. They can travel hundreds of miles from the Pacific Ocean up the Columbia River to spawning grounds in Washington, Oregon and Idaho, but did they ever make it to Montana?

That’s what fly fisherman and Anaconda resident Rob Murray wants to know.

Welcome to The Big Why, a series from Montana Public Radio driven by your curiosity about Montana.

I’m your host Freddy Monares. This is a show about listener-powered reporting. We’ll answer questions — large or small — about anything under the Big Sky. Let's see what we can discover together..

Murray says, “I’ve always wondered why there aren't salmon in the Clark Fork, just because it’s the Clark Fork of the Columbia [River].”

Freddy Monares: The Clark Fork River is one of many tributaries to the Columbia River. It flows from Butte, right through the heart of Missoula where I’m standing and on to Lake Pend Oreille in the Idaho panhandle, traveling over 300 miles in all before it connects to the Columbia via the Pend Oreille River.

Reporter Aaron Bolton is with us now to help answer this question about salmon in the Clark Fork. Hey Aaron.

This is the first time we’ve taken a listener question and before we get to answering it, can you tell us a little about Murray and why he’s been thinking about salmon in the Clark Fork River?

Aaron Bolton: Yea, so Murray is a life-long fly fisherman and he’s thought about why there aren’t salmon in the river for years. Last year, he moved back to Montana after living in Alaska for 20 years and he started fishing the Clark Fork again.

“That question came in a blizzard. For a few days we were floating the lower Clark Fork, fishing, and I asked the guys I was fishing with. None of them knew.”

FM: So why aren’t salmon making their way into the Clark Fork, even though it’s connected to the Columbia, which does have salmon?

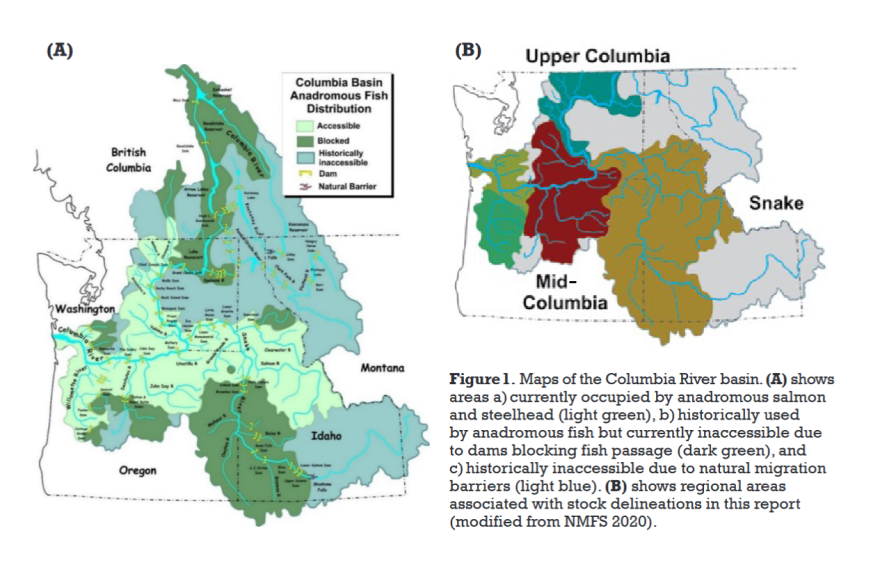

AB: When I first heard this question, my guess was that the roughly 150 dams throughout the Columbia River basin were preventing salmon from making it that far. Murray was also wondering if the dams played a role. So I started my efforts to answer his question there. Here’s the short version of what I found. The dams were first built in the 1930s as the population of the Pacific Northwest boomed.

AB: While the dams provided a ton of economic benefits, they’ve diminished salmon returns on the Columbia over the past 90 years. Now, more than a dozen salmon and steelhead trout species are endangered or threatened because of the dams.

FM: Isn’t there a push to remove these dams?

AB: Yea. Erin Ferris-Olson with the National Wildlife Federation has been helping lead a coalition of nonprofits, environmental groups and tribes who have taken the federal government to court over the damage these dams have caused to salmon returns. She says the dams have tried to modify operations to allow more fish to pass up things like fish ladders.

“It’s resulted in different efforts on the part of the Army Corps to try and increase the suitability of the habitat, increase connectivity. Those measures have not made a demonstrable impact on the salmon,” Ferris-Olson says.

AB: But, things are changing.

AB: The Biden administration in July released reports that identified dam removal as one of the best ways to restore salmon runs and outlined how the power produced by those dams in the Columbia River system could be replaced by other green sources like wind and solar. Ferris-Olson says that’s why litigation over the dams has been put on pause for now as they wait to see if any steps are taken toward dam removal.

FM: So, that seems relevant to Murray’s question. If these dams in the Columbia River are in fact removed, is there a chance we could see salmon make their way into the Clark Fork River? I guess I should ask: were they blocking salmon from entering Montana in the first place?

AB: Well, I called up Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, and the biologist I talked to said the answer was … not really. He said while dams are now preventing salmon from making it that far, there’s always been some natural feature, like a waterfall, preventing salmon from swimming into the Clark Fork River.

Idaho Fish and Game Fisheries Biologist Rob Ryan says that the impasse for salmon was somewhere on the Pend Oreille River, which connects the Clark Fork to the Columbia River. The thought was that it was somewhere near the Idaho-Washington border. Today, there’s a dam there called Albeni Falls.

“One way speculated that Albeni Falls — or a feature there at Albeni falls before the dam that’s currently built in its place — limited fish distribution,” Ryan says.

FM: So, just wanna make sure I’m understanding — the answer to why there’s no salmon in the Clark Fork is there was always some kind of natural barrier, like a waterfall, keeping them from making their way into Montana rivers?

AB: Exactly. Ryan says other fish species offer up supporting evidence for this. Below that section of the Pend Oreille River, red band rainbow trout have always been present and in the upper sections of the river; closer to the Clark Fork, those red band rainbows are replaced by cutthroat trout.

“Those types of delineations are fairly common with some of these geologic features that historically made fish distributions different above and below," Ryan says.

AB: But there is a twist here. Turns out people a century and a half ago wanted to get salmon into the Clark Fork.

FM: Wait, what do you mean?

AB: In researching this story, I stumbled upon this obscurecompilation of letters online from the late 1800s. Various chapters of the “Rod and Gun Club” in Helena, Missoula and Deer Lodge as well as a member of Idaho’s territorial legislature wrote to Martin Maginnis, who was Montana’s delegate in the U.S. House before Montana gained statehood. They wanted to clear the obstruction for salmon on the Pend Oreille River so they could swim into the Clark Fork and get into other Montana rivers. They asked Maginnis to use his sway in Congress to get approval for their plan to bring salmon to Montana.

FM: Why did they want salmon in the Clark Fork if they weren’t making their way there on their own?

AB: They talked about the economic value of the fish, estimating at the time the fisheries could be worth $200,000. That would be millions today. But keep in mind, this is long before the booming recreation economy we have around fishing for Montana’s trout today.

They also note that salmon could have been a valuable food source for Montana tribes at the time, which were struggling with the near extinction of their main food source, bison, due to the federal government’s campaign to kill off bison in order to suppress tribes.

FM: Did they actually try to remove waterfalls on the Pend Oreille in order to make this happen?

AB: It’s hard to say as I couldn’t find much more on their efforts. If they did attempt to help salmon find their way into the Clark Fork, it must have failed as we still don’t have salmon making their way from the Pacific Ocean to Montana.

FM: Ok, it seems salmon never were able to swim into the Clark Fork. So coming back to Rob Murray, who brought this question to us. What does he have to say about all this?

AB: Well, Murray was unsurprised that it was in fact a natural feature like a waterfall that prevented salmon from making it to Montana, but he was surprised by this push to help salmon make it here.

“It’s not like, 'oh man, I wish there were salmon here so I could catch them.' But at the same time, it would be really curious to see if they did do that, how things would have changed. Would they have decimated the westslope cutthroat population."

AB: Maybe we’d have much larger grizzly bears if there was a reliable salmon run in Montana. Maybe the habitat in the Clark Fork wouldn’t sustain a salmon run or maybe the same dams diminishing returns on the Columbia would have done the same on the Clark Fork.

To be clear, Murray thinks it would have probably been a bad idea, but it’s something he says he’ll ponder the next time he’s casting a line with friends.

"Yeah, cool. Now I can finally, when this question comes up, I can say 'well, I can tell ya'’”https://www.mtpr.org/the-big-why

FM: Now we want to know what makes you curious about Montana. Send us your questions and subscribe to the podcast here.