A new Montana Free Press series is shedding a light on how policies of the past and present intersect with wildfire response. Amanda Eggert, a former wildland firefighter and freelance journalist, is writing the three-part series Living With Fire. Montana Public Radio’s Aaron Bolton spoke with her about the series.

Aaron Bolton: Amanda Eggert, thanks for joining us on Montana Public Radio. I just wanted to start: what brought this series about, beyond just fire season being on the horizon?

Amanda Eggert: I used to work as a wildland firefighter. I spent four years with the Forest Service doing that, and I've always maintained an interest in policy and developments in the wildfire realm. I happen to learn a couple interesting things last year.

One was, I found a report that Headwaters Economics put out, saying that land use planning could probably be the most effective tool for preventing home losses in the wildland urban interface and maybe even more so than logging, which is frequently cited as a measure to mitigate severe wildfire.

And then I also learned about private firefighting force that's based here in Bozeman. It's the largest in the country. And that's something that I'll explore in part three of the series.

Bolton: Starting with part one of your series, it brings us all the way back to the birth of Montana's largest land manager, the Forest Service, in 1905. But it wasn't until 1910, according to your story, when the agency had its first experience with a severe wildfire, where three million acres burned in Montana and Idaho. Why was that event so significant?

Eggert: For a couple of reasons. One is that subsequent fire chiefs for the Forest Service came out of that area, the Missoula area, and fought those fires, so it was sort of seared into their memory. Another reason is it really helped the Forest Service rally public support for more funding for this fledgling agency. So, they got more infrastructure in the form of district rangers, more personnel, more lookout towers, more fire roads.

Bolton: You also go through kind of a timeline of how these policies, or how the Forest Service and some other federal agencies, were thinking about fire and how to address it. And the next significant development seemed to be the 10 a.m. policy, if you kind of want to explain when that was implemented and what it did.

Eggert: Yeah, that policy was implemented actually by a forest chief who had been on the 1910 fires. And the idea was firefighters would respond to a fire with the goal of having it out by 10 a.m. the next day. So the goal was to catch every fire when it was small.

That led to a kind of a strong preference that continued for a long time to suppress wildfire, rather than let it burn, and that was explored in later decades, particularly among the Parks Service and later the Forest Service as well.

Bolton: And what was the turning point? What made federal agencies start thinking in that way?

Eggert: I think initially, it was more just letting natural ignitions burn if the conditions were favorable, but also rolled into that later was this idea of prescribed fire, to introduce fire to the landscape, so that it could play the role that it had for centuries before it had these land managers came into existence.

Now we're in a fire deficit across much of the forested landscapes of the West. So, even though we've seen these huge fires that have developed, there are still, on the whole, more acres that need to burn in forested landscapes to restore that ecological balance that happened in the past.

Though I would also like to point out that that's not true for all landscapes across the West.

Bolton: But there are some challenges that come along with reintroducing fire to some landscapes, if you want to describe the kind of the tug of war that goes on with the idea of that.

Eggert: Yeah, sometimes it's a tough sell to the public, particularly given the air quality concerns in parts of Montana, particularly I'm thinking of the Bitterroot Valley. They have some really big wildfire seasons that result in poor air quality for up to months at a time.

And so, they sort of cherish the months of maybe June and October, when they don't have to worry so much about air quality, and they are reluctant to support prescribed burning during those months because they feel like they've already suffered from inhaling so much smoke.

[Related: Get the latest wildfire, fire management and air quality news for Western Montana and the Northern Rockies, on your radio during our morning and evening newscasts, via podcast, or in your inbox each day.]

Bolton: Part two of your series came out last week on Thursday. It focuses a lot on how communities are mitigating fire risk to homes and infrastructure in the urban-wildland interface and in some rural areas. What are some that issues happening there?

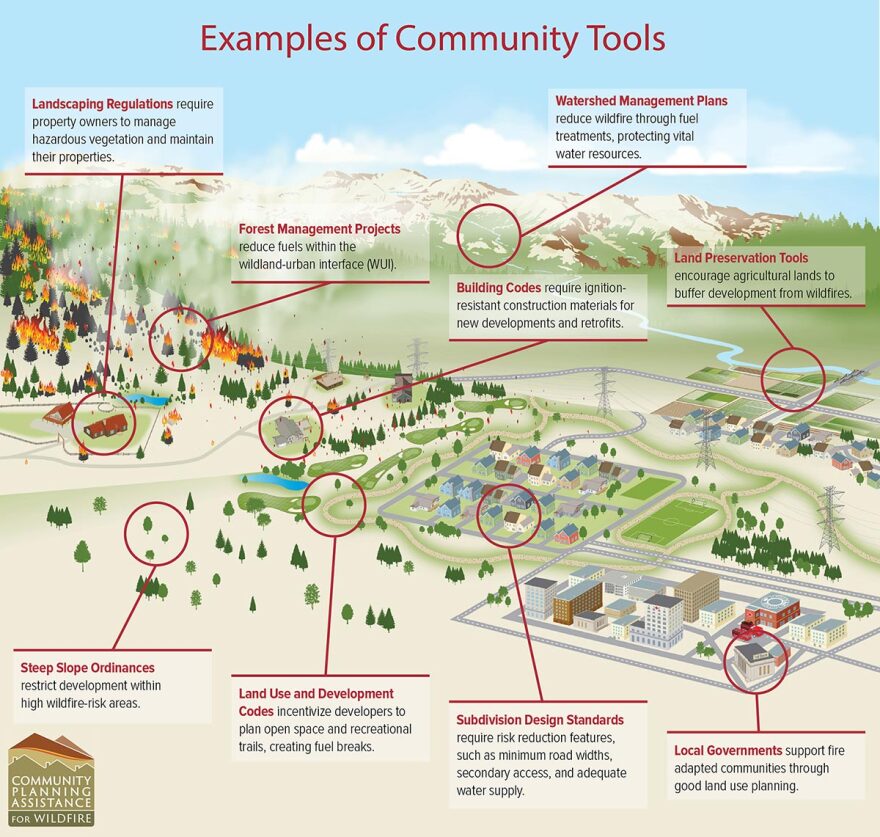

Eggert: Well, the whole approach is geared towards taking a proactive approach to planning, land use planning, so that there will be fewer losses when wildfire does come through a community.

Oftentimes, wildfires mean pretty substantial financial losses for a whole community. So, there is some incentive for a proactive approach, but zoning can be difficult to advocate for in many communities of the West.

Bolton: In this piece, you interview Ray Rasker, the executive director of Headwaters Economics, and Rasker does a lot of this kind of work with communities. Did you get a sense from him that most local governments and policymakers are thinking about this after they've gone through a wildfire or were threatened by one, kind of thinking about it after the fact?

Eggert: Yes, I think he would say that most of the communities he's worked with have suffered some pretty serious wildfire losses in recent memory. There are a few that just have really proactive land use planners and county commissioners or city commissioners that want to tackle it before it's a big issue, but generally, he says, such officials need some political cover to advocate for the kinds of change they want to make because there can be some pushback from the communities involved.

Bolton: Which communities or counties here in Montana are really being the proactive ones trying to take a lead in this?

Eggert: So far, Park, Missoula and Lewis and Clark Counties, so that would be the Paradise Valley area of southern Montana, Missoula County and then the Helena area.

Bolton: What are some of the policies that these counties have come up with?

Eggert: Missoula County passed its community Wildfire Protection Plan in 2016, and that was a much needed update to an older document, and it calls for some stricter subdivision regulations. It doesn't list them out piece by piece, but sort of gives a general framework for how they would like to grow as a county.

So, it calls for a stricter subdivision regulations. It calls for supporting prescribed burning that federal land managers are doing.

Bolton: Part two of your series was published last week. What's in store for part three?

Eggert: In part three, we're going to look at contributions that are coming from private industry, relative to wildfire. So in particular, we're going to look at a private firefighting firm that has contracts with insurance companies to protect specific properties. And they're dispatched to 20 states around the United States, and they focus only on those properties. They work within an incident command system, which is sort of the system used by the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management.

But, their focus is pretty singular. They work only to protect the properties that are covered under the insurance companies they work with.

Bolton: That's a really interesting concept. Are homeowners paying extra for this kind of protection, or is this an initiative that's coming directly from those insurance companies?

Eggert: It's coming directly from the insurance companies. For some insurance companies, I think it's a policy selling point. For others, it could be that they have a vested financial interest in preventing home losses, so they're willing to invest in these pre-suppression activities to prevent paying out a claim.

Bolton: OK. Well, looking forward to that last piece in the three part series Living With Fire. Thank you, Amanda, for joining us on Montana Public Radio.

Eggert: Thank you for having me.

Amanda Eggert is a former wildland firefighter and freelance journalist. Read the Living With Fire series here.

Get the latest wildfire, fire management and air quality news for Western Montana and the Northern Rockies, on your radio during our morning and evening newscasts, via podcast, or in your inbox each day.