Four people sat around a table in Helena Friday to start debating how to draw lines of political power on the Montana map.

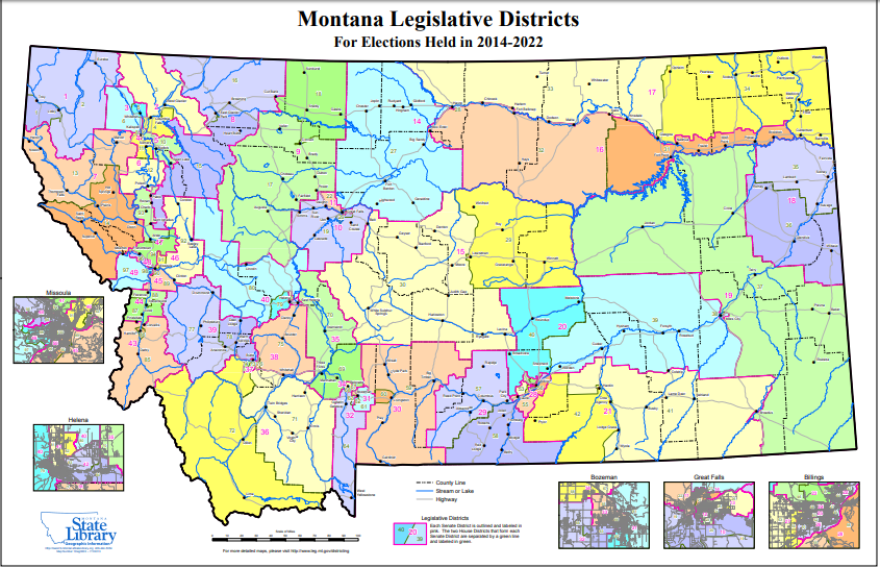

And they decided to ask for the public’s help in picking a fifth member who could cast tie-breaking votes over the lines that will shape election districts for the next 10 years. Districts for both state legislative races, and, depending on the outcome of the 2020 Census, how Montanans will elect a second Representative to the U.S. House.

“It’s highly political," says Chuck Johnson,a former long-time statehouse reporter. He’s also on the board of trustees of the Montana Historical Society.

As an example of how big a deal the nature of these political districts are, Johnson points back to a U.S Supreme Court ruling from the mid 1960s that sent Montana’s state government, and others across the country, on a new course.

“The most easily judicially maintainable standard of apportionment should certainly be population," Charles Morgan, Jr., a civil rights attorney representing Alabama voters argued in front of the U.S. Supreme Court in the landmark Reynolds v. Sims case.

At the time of the case Montana, like other states, elected their legislators in a similar model as the federal government. House members were elected by districts based on population and Senators were elected by districts based on geographical regions.

But Morgan and a group of lawyers from Alabama argued that that wasn’t right.

“In this nation there are fewer farmers than there are city people, and if you use land or if you use political units without population being the guiding factor then we must of necessity reach a representative standard that is nonresponsive to the people," Morgan said. "And the function of government should be responsive to the people which it governs.”

The U.S. Supreme Court agreed in an 8-1 opinion, establishing the one-person one-vote rule. In Alabama, the ruling expanded the political power of urban voters and African Americans.

The new rules for these legislative districts also changed Montana, Chuck Johnson says.

"Rural Montana loses its influence over the decades because it’s not growing much or losing population," he says. "Not uncoincidentally, that’s when Montana started seeing major changes.”

One of those changes was a reorganization of the state’s executive branch, which gave more power to the position of Governor. Soon after, voters called for a state constitutional convention.

Montana’s Secretary of State’s Office has pocket size Consituations sitting in its lobby area. On the first page of the little booklet it notes that only 12 of the 56 countries - the most populous counties - voted for the new Constitution.

“The ‘72 is regarded by many as the most progressive and best state constitution around," Johnson says, "some don’t agree.

"You had those two changes in the early changes, which were remarkable. And then you had in the 1970s in the Legislature you had big Democratic majorities. That’s where you saw the environmental laws passed, labor laws, human rights laws. So I think this is all somewhat related.”

Montana’s 2020 redistricting commission is in charge of redrawing the boundaries of congressional and legislative districts based on the latest population data, a process that happens every 10 years, and remains politically fraught.

The four person commission is selected, one each, by the majority and minority leaders in the state House and Senate.

“If you’re cagey you can turn a district from one party to the other just by how it’s designed," Johnson says.

This partisan tactic is known as gerrymandering.

The delegates at Montana’s Constitutional convention struggled over how to create a redistricting commission that would be free from this kind of political dickering.

According to a transcript from the convention, Delegate Richard Nutting reportedly said, "there’s real problems with possibly gerrymandering of districts and that if we can keep the membership of the commission as relatively nonpartisan as we can, and we have a lot of problems trying to arrive at how to do that.”

Jeff Essmann, a Republican appointee to the 2020 redistricting commission, read part of the transcript during the group’s first meeting today. He read comments from Delegate Carmon Skari.

“The impartiality we hope to get out of the chairman, whose vote would be the key vote here.”

The 2020 commission’s first job is to pick their chairman. But because of the even partisan split among the four appointed members they rarely agree. Only one in the last fifty years of redistricting cycles has been overseen by a chairperson agreed upon by the other commissioners.

The rest of the time the Montana Supreme Court has selected the chairperson.

Today the 2020 commissioners decided to allow the public to submit nominees for their fifth and final member, which will serve as the chairman and tiebreaker over the other four political appointees. The public comment will be taken until May 9. Details on that are available at this link.

The commission will take public input on how to break the state up into political voting districts through their redistricting planning over the next several years.

Excerpts from the oral arguments in the Reynolds v. Sims provided by Oyez, a free law project by Justia and the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.