Austin Amestoy Welcome to The Big Why, a series from Montana Public Radio where we find out what we can discover together. I'm your host, Austin Amestoy. This is a show about listener-powered reporting. We'll answer questions, large or small, about anything under the Big Sky. By Montanans. For Montana. This is the Big Why.

This week, John Hooks is back to answer our question. Welcome to the show, John.

John Hooks Thanks, Austin. Good to be here.

So, before I tell you this week's question, I want to take you to a little frontage road just outside of Great Falls.

All right. I'm looking down at launch facility I-11 of the 10th Missile Squadron.

Austin Amestoy Wait, that was missile squadron? Like nuclear missiles?

John Hooks That's right. Across Montana there are hundreds of nuclear missile silos and launch facilities hidden in plain sight. A lot like this one. Just kind of a small fenced off area. Well, if you didn't know what you were looking for, probably woulddn't know what it was.

Austin Amestoy So I remember hearing a lot about these missile sites during that whole recent Chinese balloon debacle. But why are we talking about them for this episode?

John Hooks That's because our listener question this week is why? Why are there so many nuclear missiles scattered over central Montana?

Austin Amestoy Okay, so where do we start?

John Hooks Well, first we got to dig into how they got here in the first place. The weapons here in Montana are intercontinental ballistic missiles or ICBMs. And the origin of those dates back to the height of the Cold War in the 1950s and '60s, specifically the Soviet launch of the Sputnik satellite in 1957.

[Archival news footage] Today, a new moon is in the sky. A 23 inch metal sphere placed in orbit ...

John Hooks Sputnik kicked off a whole new phase of the conflict and triggered a deluge of military spending to ramp up our own missile technology in competition with the Soviets. At that time, the focus was on building as many missiles as we could, as quickly as we could.

Matt Korda Counterintuitively, the weapons came first and then the questions of how and when to use them came second.

John Hooks That's Matt Korda.

Matt Korda I'm a senior research associate project manager for the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists.

John Hooks Korda says that the rationale that the military and the government came up with was this idea of a nuclear triad; basically, that America needs to have nuclear capability from air, land and sea, with the ICBMs being the land portion. The military still argues to this day that having the ability to strike from so many places deters attacks from potential adversaries because America has all these different ways of ensuring that we could retaliate.

Austin Amestoy All right. That explains the origin of these missiles. But why did the military place them in Montana?

John Hooks Well, to get the answer to that, we have to take a field trip.

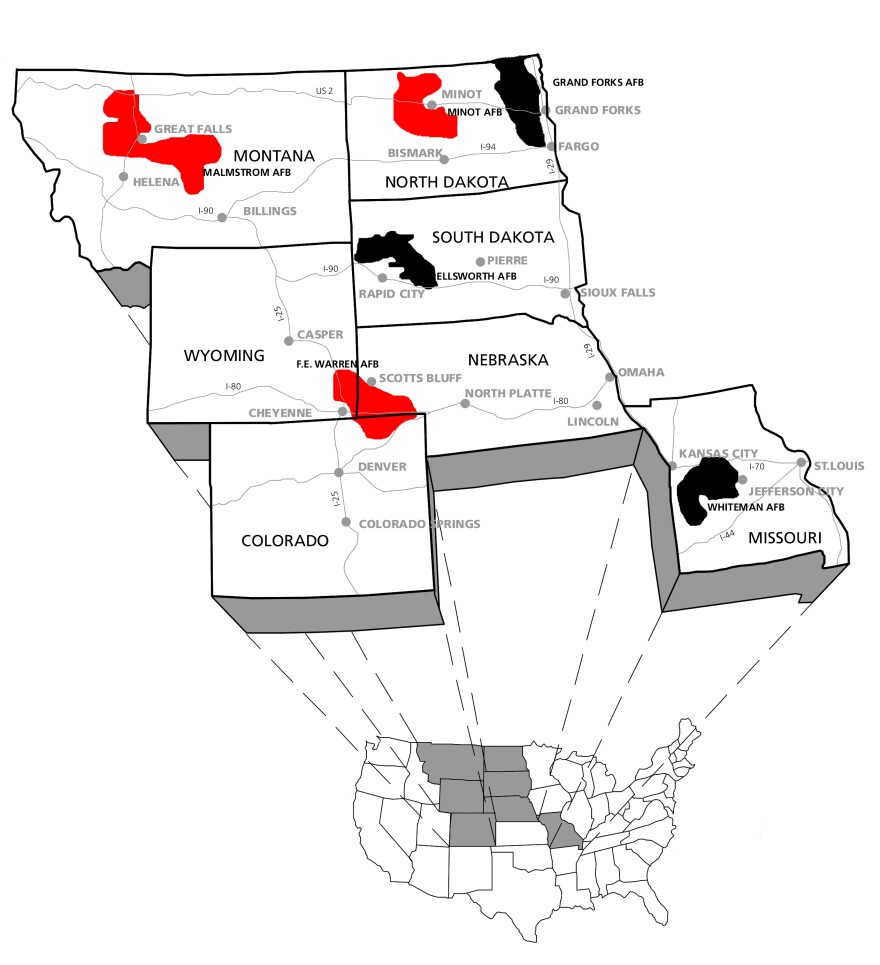

I am on Malmstrom Air Force Base right now. Just passed through all the security checkpoints and we are driving into the museum and air park, a big field with a bunch of old planes, and conspicuously, one big former nuclear missile. I went up to Malmstrom to interview Dr. Troy Hallsell. He is the official historian of the 341st missile wing, which is the unit of the Air Force that maintains and operates the missile sites in Montana. Dr. Hallsale told me that the missiles arrived in Montana once the military and defense contractors had successfully developed a missile called the Minuteman, which the Air Force decided to install in five missile wings across the middle of the country. One of those spots was in Montana. Here's Dr. Hallsell.

Troy Hallsell So, the reason that the Air Force selected to get Montana and the Great Plains is that it needed big, wide, sparsely populated stretches of land to build this weapon system.

John Hooks Initially in Montana, they put in 150 launch facilities, but each of these facilities had to be far enough apart to make sure the system could survive If one or more of the sites were hit by an enemy attack.

Troy Hallsell They had to space each launch facility between 3.5 And 17.5 miles away from its launch control center. And each launch facility, 3.5, two 8.5 miles apart from one another.

John Hooks This strategy of placing ICBMs in low population Western states was also part of a government decision that in the event of a nuclear attack, it would be better to draw enemy fire to places where fewer people lived. Anti-nuclear activists actually came up with a pretty colorful term to describe this strategy, calling these states America's "nuclear sponge."

Austin Amestoy Wow, that's a pretty dark term. What was the timeline of building the facilities and actually putting the missiles in?

John Hooks This was all going on in the early '60s. And there's some important context here.

[President Kennedy archival tape] This government, as promised, has maintained the closest surveillance of the Soviet military buildup on the island of Cuba.

John Hooks The first missiles in Montana were armed right at the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis, and about a year later, JFK himself actually came to Great Falls to celebrate the job being done.

[President Kennedy archival tape] We are many thousands of miles from the Soviet Union, but this state, in a very real sense, is only 30 minutes away.

John Hooks Luckily for all of humanity, the missiles were never used, but they stayed in place, eventually just blending into the landscape.

Mary Hooks It was kind of a matter of fact to me because I was too young to appreciate the seriousness of what was going on. But they just were always part of our life.

Austin Amestoy And who's that we're hearing from?

John Hooks Well, actually, that's my mom.

Mary Hooks I'm Mary Hooks, and I was born in Great Falls, Montana, in 1956.

John Hooks She grew up in Great Falls in the era that all of this was going on. And my late grandfather was actually an air traffic controller over at the Air Force base. I talked to her to get a sense of how these weapons fit into people's daily lives.

Mary Hooks We had drills where we would have to duck and cover under the desks in school, and those were nuclear drills. And it's kind of funny how something like that that's so serious could just become kind of matter of fact every day thing, you know?

Austin Amestoy Something else I'm curious about, John. What's the status of Montana's missiles today?

John Hooks So there are still about 100 missiles in Montana, but they're getting pretty old. The last update to the missiles themselves was in the '70s and the facilities are essentially the same ones installed in the '60s.

Austin Amestoy So what's the plan going forward then? You know, is the military going to phase these weapons out?

John Hooks The Air Force has actually locked- in a plan to spend about $400 billion updating all the facilities and replacing the missiles with a new system.

Austin Amestoy Wow. That is a big chunk of change. Why does the Air Force say this is necessary?

John Hooks The military says these nukes are still a needed deterrent. And Montana's congressional delegation and the local governments in the counties where these missiles are located are almost universally in favor. But Matt Korda looks at it differently, comparing this new project to the initial development of the ICBMs that we discussed earlier, where the emphasis is all on building these weapons and then rationalizing it afterward.

Matt Korda It's almost like the system is like on autopilot. These things, because they exist, they naturally need a follow-on system. After this system, there will probably be another follow-on system, right? And then another one.

John Hooks And he questions whether all that money wouldn't be better spent in other areas.

Matt Korda Would people really be any safer with these weapons or actually are they perhaps less safe with them?

Austin Amestoy Well, John, they're just one last thing I'm curious about here. Did you ever get hold of the listener who asked this question and what did they think about what you found out?

John Hooks Yeah, I did. But as it turns out, I would not have been able to tell them anything they didn't already know.

Troy Hallsell So we walk over there, so I'll go ahead and tell you I was the person that submitted the question.

John Hooks Were you really? Yeah.

Austin Amestoy Wait. Dr. Halsell was the one who asked the question.

John Hooks Yeah. Turns out he's a fan of the show. He said he gets asked about nukes all the time and thought it was a good question for our format.

Austin Amestoy Well, we do always love hearing from our fans. Thanks for diving into this story, John.

John Hooks My pleasure.

Now we want to know what makes you curious about Montana. This show is all about answering your questions, so send them to us below or at www.mtpr.org/bigwhy. Find us wherever you listen to podcasts and help others find the show by sharing it and leaving us a review.

-

Elk are a familiar sight in much of Montana now, but that hasn't always been the case. By the early 1900s, unregulated hunting had led to massive declines in wildlife nationwide. But In Yellowstone, elk populations were exploding thanks to protections in place there. The solution to restoring elk outside the park seemed obvious. Less obvious was how to make it happen. This week on the Big Why, we trace the animals' bumpy path from the living laboratory called Yellowstone Park to the Bitterroot Valley and beyond.

-

If you’ve been to a taproom, you know that at most breweries across the state there’s a three pint limit and they stop serving at 8 p.m. One listener wants to know why. We've got answers. Pull up a stool, crack open a local brew and settle in for a taproom tale – or some barroom banter, depending on the time of day.

-

When it comes to winter driving, everyone wants their route clear and dry, and they want it done quickly. Why don't the plows come sooner or more often? Why don't they drop more salt or deicer? Why not get more drivers on the road? Tag along as a Montana snowplow driver prepares for a big winter storm and find out more about the logistical, environmental and technical challenges that come with keeping the roads clear of snow.

-

How do cabbage and spices become ingredients for community building? In Korea, the answer is kimjang, the fall tradition of making and sharing kimchi. This week on The Big Why, we visit a farm in the Bitterroot Valley where a group of Montanans came together to keep a food custom alive and find comfort and connection among the cabbage.

-

In Montana, abortion access has been at times illegal, legal, and stuck in limbo. Providers have weathered bombings and arson, advocates and opponents have battled it out in court, and citizens have passed a constitutional amendment affirming a woman's right to choose. One listener wants to know more about the history of reproductive rights in Montana. MTPR's Aaron Bolton reports on the underground networks, political violence and landmark court cases that got us to where we are today.

-

A flag's primary purpose is to be recognized from a distance. That means few colors, no lettering and a clear distinction from other flags. Ideally, it should be simple enough for a child to draw it from memory. So, how did Montana end up with such a complicated flag? Learn more in this episode of The Big Why.