Property taxes are the primary way Montanans pay for local government services including schools, law enforcement and fire departments, among other things. But the math used to calculate them can be quite complex, making it hard to understand who’s paying how much and why. It can also be hard to know what’s going to happen to your taxes when your home’s value rises.

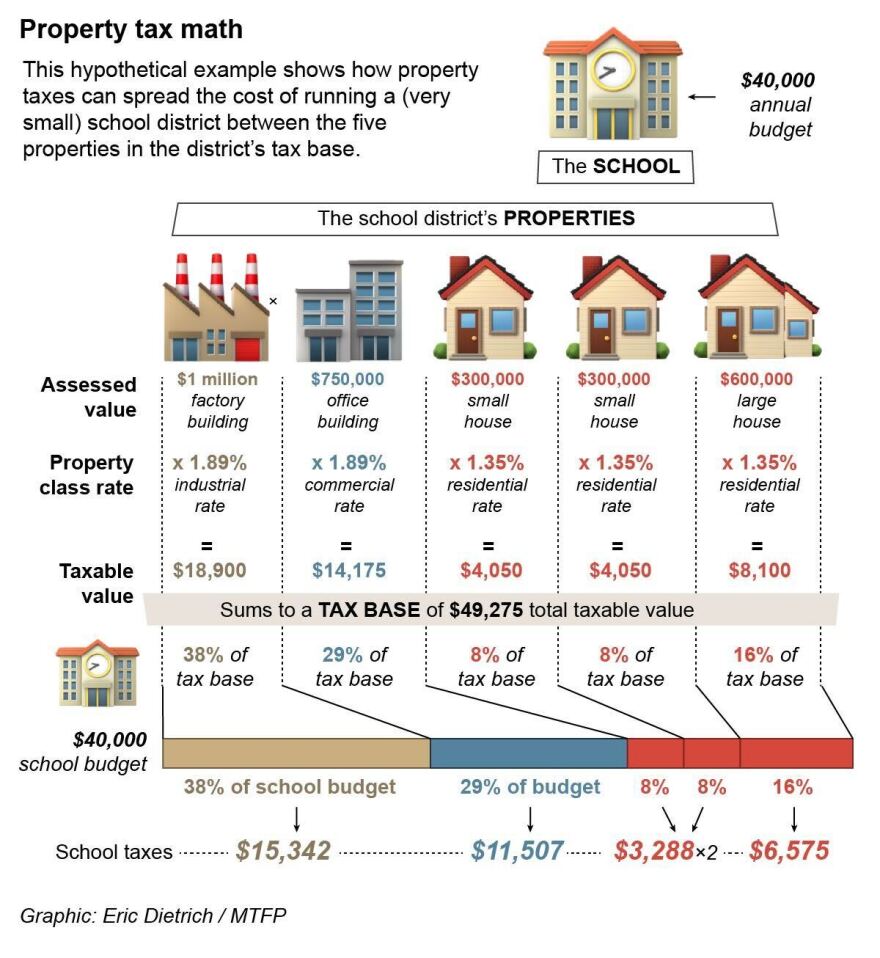

In the hope of providing some clarity, here’s a simplified model of a Montana school district.

It has one school.

Let’s say the school costs $40,000 a year to run. That’s a very inexpensive school — but, as you’ll see, it serves a very small district.

In the real world, schools are funded by money from many sources, including the state and federal governments. For the sake of keeping this example simple, let’s say this one is funded only by local property taxes.

This is the school district.

The district includes a factory, one office building and three houses (one of them a bit bigger than the other two). Those properties compose the tax base that the school district can draw on to fund its operations.

The tax system divides the cost of the school budget among the properties in the tax base. Here’s how that math works:

1) The assessed value of each property is estimated by the Montana Department of Revenue. That can be a complicated process, but most homes are assessed at the department’s best estimate of what they would sell for on the current market. In most cases, property values include the value of both structures and the underlying land.

2) The assessed value is multiplied by a property class rate to produce its taxable value. The property class rate is different for different types of property (a complete list is here). The commercial properties in our example are converted to taxable value at a higher rate, 1.89%, than the residential properties, which are converted at 1.35%. Those rates are set by the Legislature to balance tax burden between different types of property.

3) Tax bills are allocated proportionally to each property’s share of the tax base. This is typically done by calculating millage rates (more on those in a bit), but the important thing to understand is that your taxes are proportional to your taxable value. So, for example, a home that represents 8% of the tax base is responsible for 8% of the school budget. Of course, in the real world, with many more taxable homes and businesses in a school district, your share of the school budget is much smaller.

A couple of things to note here: This math means that residential properties worth the same amount pay the same amount — as is the case with the two $300,000 homes in our simple example. And more expensive homes, such as our $600,000 house, pay more.

So what happens if property value assessments go up — as they have across Montana in recent years? Let’s first look at what happens if every property within the tax base doubles in value:

As it turns out, when assessed values rise evenly across the board, everyone’s share of the school bill stays the same. That’s because what matters isn’t your absolute property value, but instead the proportion of the tax base your property represents.

So does that mean you should rest easy if the state department of revenue has told you your home value spiked this reappraisal cycle? After all, your neighbors’ values are probably headed up too.

Well, maybe. Because things are of course a bit more complicated than that.

For starters, let’s see what happens when residential home values rise faster than other types of properties — a dynamic that’s common in communities across Montana right now. For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume home values in our example school district double, while the factory and office properties stay constant at their original level.

When home values rise faster than other types of property, tax burden shifts from those other property classes onto homeowners and landlords who rent out residential properties. Again, that’s because taxes are levied proportionally to each property’s share of the tax base.

Secondly, let’s look at what happens when that school budget grows. Let’s say the school board votes to give the school’s only employee a raise that bumps the budget to $45,000. (That’s a 12.5% increase.) Let’s also assume property values stay constant:

This one is pretty straightforward. All property owners pay 12.5% more, proportional to the spending increase.

Let’s do one final example where the factory is closed, reducing its property value to zero. Again, let’s assume other property values and the school budget stay constant.

With the tax base significantly smaller, the portion of the school budget that was previously paid for by the factory owners now shifts to the district’s commercial and residential properties. That substantially increases their tax bills.

Conversely, new development — such as home construction, or a new hotel being built in the district, grows the tax base, spreading the cost of running local services across more properties. However, growth also typically brings higher bills for local governments (e.g., more kids to teach, which means hiring more teachers and maybe building a bigger school) — so taxpayers don’t necessarily come out ahead when a district’s tax base grows.

In the real world, shifts like these are happening an on ongoing basis across Montana’s hundreds of thousands of individual properties, combining in ways that can be baffling to researchers and elected officials — much less to individual taxpayers. Additionally, taxpayers have to contend with multiple taxing jurisdictions layered on top of one another.

If you look at your tax bill (or your landlord’s, which you can often look up online if you’re a renter), you’ll probably see a stack of different line items contributing to the total at the bottom. Sometimes you’ll see those items expressed in terms of “millage rates” or “mills.”

Mills are a source of endless confusion for public officials, taxpayers and journalists tasked with writing about tax policy. But they’re essentially just a way of describing tax rates, an indication of how much tax is owed for each dollar of property’s taxable value. Mills are usually expressed as dollars owed per thousand dollars of taxable value (hence the name “mills,” which is derived from the Latin word for “thousand”).

Mills are calculated by dividing the total amount of money a school district or other tax jurisdiction wants to collect by the value of its tax base, then multiplying that by 1,000.

So for our original school example above:

That means the school district is levying 812 mills of property taxes. You can calculate each property’s school tax by applying that millage rate to its taxable value:

Note that you have to divide by 1,000 in these calculations to strip out the mill factor.

In the real world, some property taxes are actually defined in terms of mills. The Montana University System’s six-mill levy, for example, levies six mills worth of taxes to help fund public colleges. The state also collects 95 mills of taxes to equalize funding between rich and poor school districts (this is one of the details we’re neglecting with our example district’s simplified budget).

Unlike most local taxes, which are based on taxing jurisdiction budgets and then translated into mills for tax bills, mill-based taxes do scale directly with property value increases. If your assessed property value doubles, you’ll be responsible for paying twice as much into Montana’s six-mill higher education levy, for example.

Here’s a how layered taxes from multiple government entities combine to build a hypothetical tax bill for one homeowner in our example district:

Stating taxes in terms of mills means you can add the rates assessed by different taxing entities together to get a combined tax rate — 1,713 mills in our example. Because of the way math works, applying that combined rate to your property’s taxable value gives you the same total tax as calculating each tax line individually and summing the result.

One last thing to address before we’re done: If you’re a Montana homeowner who’s trying to take the information in this piece and square it with the various property tax documents you get in the mail, you should know that there are a couple of different entities involved in administering the property tax math.

First, appraising your property — determining the assessed value used for these calculations — is the responsibility of the Montana Department of Revenue. The revenue department, which reports to the governor and has branch offices scattered around the state, reappraises residential properties every other year.

Your tax bill, however, is calculated by your county treasurer, who combines the state appraisals with the budgets passed by county commissioners, city councilors and school board trustees. Property tax payments are due in Montana twice a year, in November and May. If you have a mortgage, the actual payments are likely processed through your bank, which typically bundles taxes with your monthly mortgage payments.

If you’re a Montana homeowner reading this piece in summer 2023, you’ve likely received a reappraisal notice from the Montana Department of Revenue — and, given how much home prices have grown in recent years, it probably tells you your taxable value has gone up significantly.

Those reappraisal notices include an estimate for your next annual tax bill, which will show it increasing proportionately to your home value. But if you call your county treasurer and ask, they’ll probably tell you that the state’s estimate won’t be what you see when they send your actual tax bill out this fall.

Here’s why: If you look closely at the fine print, the 2023 appraisal notice will tell you that its tax estimate is based on your new taxable value and last year’s millage rate. Last year’s millage rate, however, is based on last year’s taxable values. And, when property values have risen dramatically across the board, that means the current year’s tax base is going to be much larger than last year’s — just like in our ‘Case 1’ example above.

All that means taxing jurisdictions like our little school district will, in theory, be able to assess fewer mills of taxes, assuming they hold their budgets constant.

Furthermore, state law caps how quickly local governments can expand their tax collections, limiting the growth of taxes cities and counties can collect on existing properties to half the rate of inflation. That statute exempts new developments coming onto the tax rolls, as well as voter-approved tax increases. It also doesn’t cover some non-tax fees.

The long and short of all that? If you’ve received a reappraisal notice saying your property value has risen by 30, 40, or 50% or more, that doesn’t necessarily mean your taxes will rise that much — because most other Montana taxpayers are in the same boat. You won’t know for sure, however, until your county treasurer sends you your tax bill this fall.

There’s plenty more that could be explored about what goes into your final tax bill — the state’s property tax assistance programs, for example, or how you can appeal your tax valuation if you think it’s wrong, or (if you really want to get into the weeds) the tax increment finance districts that, in some parts of the state, divert some property tax dollars to economic development efforts.

Let’s leave things here for now though. If you have further questions or would like better clarity on some of the questions addressed here, please reach out at edietrich@montanafreepress.org.

Have questions about your reappraisal notice once it comes in? Are you a homeowner worried about what higher taxes mean for your family’s budget? A landlord pondering whether you need to pass higher taxes onto your tenants? Someone else who has insight worth sharing with other folks across Montana? Montana Free Press would love to hear about it as they cover what the reappraisal cycle means for Montana taxpayers and the public institutions they fund. Take a brief survey here.

This story comes courtesy of Montana Free Press.