The State Department is promising Congress a reply to allegations that the vast, new U.S. embassy project in Baghdad is so riddled with construction and safety problems that officials can no longer even predict when it might be ready for use.

Critics say the problems stem from a system that allowed subcontractors to skim money at every level and left the job to an ill-paid work force that may have included illegally trafficked foreign workers.

The demand for answers came from Rep. Henry Waxman (D-CA), the chairman of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform.

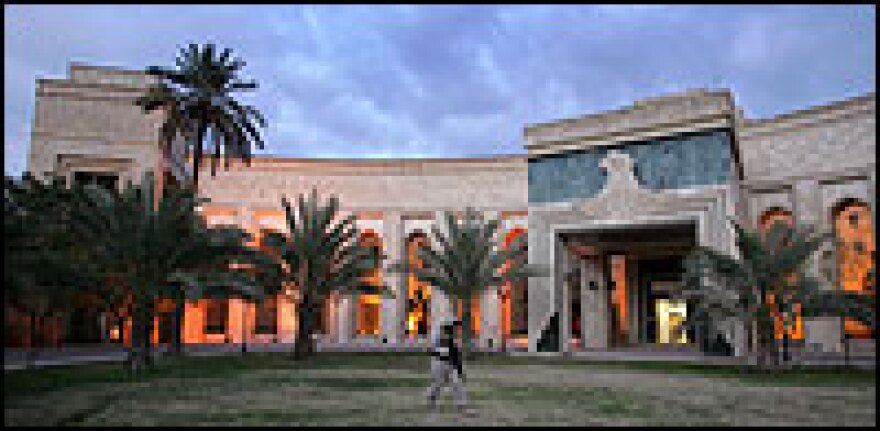

He has been holding hearings on the cost and quality of the $600 million project, which is to be the biggest U.S. embassy in the world. In a letter to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, Waxman noted that the 21-building complex was not finished in September, as promised, and that its opening has now been delayed indefinitely.

In response, the State Department has promised to provide documents and briefings from Ambassador Patrick Kennedy, the head of management policy, and Charles Williams, the official in charge of building embassies overseas.

State Department Responds to Criticism

At a hearing this summer, Williams, a retired major general, boasted that the embassy complex was "among the best" projects that his office has managed.

Less than three months later, the State Department announced that the embassy would need another $144 million worth of work, and Waxman's committee learned that its electrical and fire-protection systems had repeatedly failed inspections.

The immediate State Department response to the allegations came from spokesman Sean McCormick, who said the fuss over the project was "ridiculous."

He compared the inspection failures to items on a contractor's "punch list," a fairly routine list of items that need to be fixed or changed before a project is accepted by the buyer.

McCormick said the additional $144 million price tag was not a cost overrun, but "an additional contract requirement." He said it would cover additional secure office and living space for personnel at the complex.

Questions Raised About Subcontractor

Pratap Chatterjee, the executive director of the business watchdog group CorpWatch, says the State Department was already overwhelmed by the chaos in Iraq when it was asked to do "something impossible. ... Orders came down from on high that said, 'Build us an embassy that will be impregnable.'"

Chatterjee says the Bush administration, already criticized for the multimillion-dollar, no-bid contracts it gave to companies such as Halliburton, was under pressure to find a local contractor for the embassy job.

"They chose a Halliburton subcontractor, First Kuwaiti," Chatterjee said. "[The company] had shown [that] they were very good at producing thousands of laborers at short notice but had no experience with this kind of job."

First Kuwaiti Trading and Contracting is owned in partnership by Lebanese businessman Wadih Al-Absi and Mohammed Maarafi, a member of a powerful Kuwaiti banking family. Worth about $35 million in 2003, the company says it has done more than $1 billion worth of business in the region this year alone. Most of its projects are involved in Iraq and funded with U.S. government money.

Middle Eastern Subcontracting System

Chatterjee says that part of the problem with the embassy lies in the Middle Eastern system of subcontracting, in which many levels of contractors may take a cut of the money before any actual work is done.

U.S. investigators have complained that this system also makes it difficult for them to probe through the layers of subcontractors to find out about real costs. Chatterjee says the final work goes to contractors who make the least money and have an incentive to cut costs and hire unskilled labor.

American construction supervisors who have testified before Waxman's committee have said that they saw little in the way of professional supervision at the embassy building site.

They also said they saw people they believed to be trafficked laborers — workers who had been promised hotel jobs in Kuwait, but then were forced to do construction jobs in Iraq.

Who Will Foot the Bill?

It's not clear at this point who will pay for redoing the faulty work in the original construction. It will be costly, because it involves water pipes that must be dug from ground that has already been paved over and electrical wiring that must be ripped from finished walls. Disputes over cost overruns and contract performance can take years to resolve, and there are ongoing criminal fraud investigations.

In the meantime, nearly 1,000 American diplomats, staff members and military personnel are working in a warren of crowded offices in one of the palaces built by Saddam Hussein, itself a model of shoddy construction.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.